Guardianship Gulag

One former nurse was so enraged by Fort Worth’s probate court that she wrote a book about it.

12

Posted April 13, 2016 by Static in News

Few newspapers have published more stories on probate courts and guardianship cases gone wrong than yours truly. Tarrant County’s probate courts, led by Judges Pat Ferchill and Steven King, hear difficult cases, for sure. But the Fort Worth Weekly has spotlighted numerous instances in which people have been stripped of their rights and removed from their homes with little justification. Associate Editor Jeff Prince has written a dozen stories, beginning with “Saving Katia” on July 2, 2008, and as recently as “Torn Apart” on March 16, 2016. He has described how a powerful system of judges, attorneys, bankers, and care providers are overstepping the limits of decency if not legality.

More and more newspapers nationwide have begun scrutinizing their own probate courts and guardianship systems. In Texas, the Austin American-Statesman, Houston Chronicle, and San Antonio Express-News are providing the best coverage among mainstream dailies. A San Antonio-based grassroots coalition of activists known as G.R.A.D.E. is relying on social networking to build up their numbers and push for probate reforms. They and other people make frequent trips to Austin to speak at legislative hearings. And why shouldn’t they? Ferchill and other judges attend public hearings to speak in favor of laws that give them more power to tear apart families in the name of greed.

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram has been more of a cheerleader to the courts than anything. The paper has published stories depicting families who are happy about the court intervening in sticky situations. The paper has written puff pieces about judges. That’s fine –– good things do happen in probate courts sometimes. But the paper has pretty much ignored the questionable decisions being made on a regular basis inside those courtroom walls.

You know who isn’t ignoring Tarrant County’s guardianship system any longer? Susan Hodges.

Who is she?

Well, there is no reason you would know her. Until recently, she was just a retired nursing home administrator living the slow and easy life in Fort Worth. But something nagged at her. No, it was more than nagging. She has been haunted for years. Her conscience had declared war on her and was using razor-barbed guilt as its primary weapon of torture. Hodges worked at several nursing homes over the years, but it was her time spent in a Fort Worth facility that created her many sleepless nights. Her dealings with the local guardianship program showed her that the judges, attorneys, and caseworkers were more interested in power, control, and money than in doing what’s best for people.

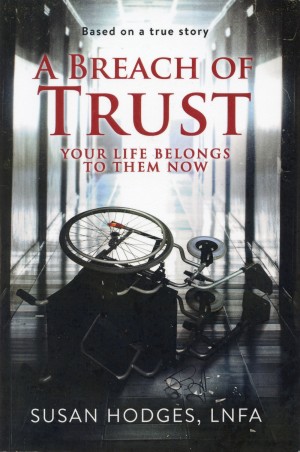

Hodges felt guilty about being unable to protect some of her nursing home residents from decisions made by the local judges and court-appointed lackeys. So she wrote and self-published A Breach of Trust: Your Life Belongs to Them Now, her book “based on a true story” about dealing with the local probate courts.

“It took me this long to write it because I’m scared to death of that court,” Hodges said. “All the other nursing homes I worked in, none of this happened. There is something with [Fort Worth’s] guardianship program that I don’t understand. I don’t want to deal with these people again.”

Hodges based her book’s stories and characters on real events and people, although she used fictitious names. Some characters were composites of different people. But the nuts and bolts of the story were true, she said, including the part about the local guardianship system being a nightmare for people who have the misfortune of becoming elderly and vulnerable. In the book, the author connects heavy-handed tactics of the guardianship system with the premature deaths of patients. And while the first-time author is no Ken Kesey, her book is comparable to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in the outrage it inspires against institutional abuses.

Tarrant County guardianship administrators would take control of patients via the probate judge’s rulings. Then, if nursing homes or other institutions did not do exactly as told, the guardians would move the patients somewhere else, Hodges said.

“The courts are very ignorant about what a nursing home is all about,” she said.

Nursing homes become small communities with groups of people forming deep friendships that, in some cases, improve their physical and mental wellness. The probate court seemed to consider money first when making decisions about when and where to move clients, she said. This is hard on old people, who get used to nurses, food, and surroundings. They become close to one another.

“The residents usually start loving the home, and they’re proud of it,” she said.

She recalled supervising a nursing home that was adjacent to another nursing home, and the residents in both homes acted like students at rival high schools, competing with each other to be the best.

But the probate court sees the residents as commodities rather than human beings, she said.

“It’s very gut-wrenching,” Hodges said.

Old people can die quickly when they’re ripped away from their community. Hodges saw it happen. That’s what haunted her the most.

“I’m supposed to be protecting these people,” she said. “I never took another court-appointed [client] from Fort Worth again.”

Later, she left Fort Worth and worked at nursing homes in rural areas.

“You don’t see this in rural areas,” she said.

Why not?

Well, people in rural areas know one another. They run into each other at dinner, at school, at church. If a judge tries to force people into guardianship cases to remove their rights and take control of their lives and bank accounts, every person around hears about it. That judge is unlikely to be reelected.

Tarrant County has almost two million people, making it much easier to destroy lives in anonymity.

Hodges said she complained to the Texas Department of Aging and Disability Services, the agency that licenses and regulates care providers.

“I was told, ‘Hands off.’ DADS does not get involved in anything with the court,” she said. “I got no answers. Everything should be about the residents and not about us and our agendas.”

She wrote the book to warn people about the guardianship program while assuaging her guilt.

“I’m not an author,” she said. “I never intended to write a book. But that’s how much this affected me. This program needs scrutiny. They do what they want. They are protected by the judges. We’re at their mercy.”

The afterword of Hodges’ book credits articles written by Prince as an inspiration for her book. “Check them out,” she writes, “and see the real faces of the folks who have been sucked up by this scheme.”

The book is available at Amazon.com and at Hodges’ website: www.abreachoftrust2016.com.

More and more newspapers nationwide have begun scrutinizing their own probate courts and guardianship systems. In Texas, the Austin American-Statesman, Houston Chronicle, and San Antonio Express-News are providing the best coverage among mainstream dailies. A San Antonio-based grassroots coalition of activists known as G.R.A.D.E. is relying on social networking to build up their numbers and push for probate reforms. They and other people make frequent trips to Austin to speak at legislative hearings. And why shouldn’t they? Ferchill and other judges attend public hearings to speak in favor of laws that give them more power to tear apart families in the name of greed.

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram has been more of a cheerleader to the courts than anything. The paper has published stories depicting families who are happy about the court intervening in sticky situations. The paper has written puff pieces about judges. That’s fine –– good things do happen in probate courts sometimes. But the paper has pretty much ignored the questionable decisions being made on a regular basis inside those courtroom walls.

You know who isn’t ignoring Tarrant County’s guardianship system any longer? Susan Hodges.

Who is she?

Well, there is no reason you would know her. Until recently, she was just a retired nursing home administrator living the slow and easy life in Fort Worth. But something nagged at her. No, it was more than nagging. She has been haunted for years. Her conscience had declared war on her and was using razor-barbed guilt as its primary weapon of torture. Hodges worked at several nursing homes over the years, but it was her time spent in a Fort Worth facility that created her many sleepless nights. Her dealings with the local guardianship program showed her that the judges, attorneys, and caseworkers were more interested in power, control, and money than in doing what’s best for people.

Hodges felt guilty about being unable to protect some of her nursing home residents from decisions made by the local judges and court-appointed lackeys. So she wrote and self-published A Breach of Trust: Your Life Belongs to Them Now, her book “based on a true story” about dealing with the local probate courts.

“It took me this long to write it because I’m scared to death of that court,” Hodges said. “All the other nursing homes I worked in, none of this happened. There is something with [Fort Worth’s] guardianship program that I don’t understand. I don’t want to deal with these people again.”

Hodges based her book’s stories and characters on real events and people, although she used fictitious names. Some characters were composites of different people. But the nuts and bolts of the story were true, she said, including the part about the local guardianship system being a nightmare for people who have the misfortune of becoming elderly and vulnerable. In the book, the author connects heavy-handed tactics of the guardianship system with the premature deaths of patients. And while the first-time author is no Ken Kesey, her book is comparable to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in the outrage it inspires against institutional abuses.

Tarrant County guardianship administrators would take control of patients via the probate judge’s rulings. Then, if nursing homes or other institutions did not do exactly as told, the guardians would move the patients somewhere else, Hodges said.

“The courts are very ignorant about what a nursing home is all about,” she said.

Nursing homes become small communities with groups of people forming deep friendships that, in some cases, improve their physical and mental wellness. The probate court seemed to consider money first when making decisions about when and where to move clients, she said. This is hard on old people, who get used to nurses, food, and surroundings. They become close to one another.

“The residents usually start loving the home, and they’re proud of it,” she said.

She recalled supervising a nursing home that was adjacent to another nursing home, and the residents in both homes acted like students at rival high schools, competing with each other to be the best.

But the probate court sees the residents as commodities rather than human beings, she said.

“It’s very gut-wrenching,” Hodges said.

Old people can die quickly when they’re ripped away from their community. Hodges saw it happen. That’s what haunted her the most.

“I’m supposed to be protecting these people,” she said. “I never took another court-appointed [client] from Fort Worth again.”

Later, she left Fort Worth and worked at nursing homes in rural areas.

“You don’t see this in rural areas,” she said.

Why not?

Well, people in rural areas know one another. They run into each other at dinner, at school, at church. If a judge tries to force people into guardianship cases to remove their rights and take control of their lives and bank accounts, every person around hears about it. That judge is unlikely to be reelected.

Tarrant County has almost two million people, making it much easier to destroy lives in anonymity.

Hodges said she complained to the Texas Department of Aging and Disability Services, the agency that licenses and regulates care providers.

“I was told, ‘Hands off.’ DADS does not get involved in anything with the court,” she said. “I got no answers. Everything should be about the residents and not about us and our agendas.”

She wrote the book to warn people about the guardianship program while assuaging her guilt.

“I’m not an author,” she said. “I never intended to write a book. But that’s how much this affected me. This program needs scrutiny. They do what they want. They are protected by the judges. We’re at their mercy.”

The afterword of Hodges’ book credits articles written by Prince as an inspiration for her book. “Check them out,” she writes, “and see the real faces of the folks who have been sucked up by this scheme.”

The book is available at Amazon.com and at Hodges’ website: www.abreachoftrust2016.com.